BY BEN BARSKY

Patrick is a visual artist working primarily with themes related to identity, history and gender politics. Through the retrospective and interview we explore those themes with him in more detail and he also gives us a fascinating insight into his process through a series of development images. Read the full feature at Artisan Idea.

I LOVE STORY TELLERS AND MUSICIANS WHO TAP INTO THEIR PERSONAL EXPERIENCES AND PAIN TO MAKE ART THAT’S VISCERAL AND CONSCIOUS.

BEN BARSKY: I always find in interesting where the artists choose to start their retrospectives. Some go right back to their teenage work (sometimes even further) while other start from an early important piece. In your case it was the latter. What was your work like before Imperfect Colossi? Were there other specific themes you were exploring or was it just painting for paintings sake and developing your skills? It would be interesting to see 1 or 2 examples from that period.

BEN BARSKY: I always find in interesting where the artists choose to start their retrospectives. Some go right back to their teenage work (sometimes even further) while other start from an early important piece. In your case it was the latter. What was your work like before Imperfect Colossi? Were there other specific themes you were exploring or was it just painting for paintings sake and developing your skills? It would be interesting to see 1 or 2 examples from that period.

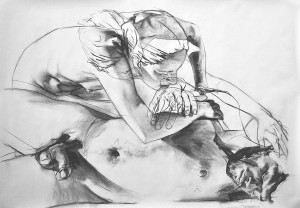

PATRICK EARL HAMMIE: Before Imperfect Colossi, most of my works were drawings that explored similar themes. During that time I made a decision to transition from drawing to painting, spending a good deal of time learning how to utilize oil paint. I would practice working in various traditions of the past. As I mastered them, I would take on portrait commissions to support my practice. Sadly, I don’t have many examples of those exploratory pieces.

BB: At what point did the interest in working to such a large scale enter your work? What is the appeal of that?

PEH: Ever since college I’ve been drawn to working large scale. As a freshman, I remember seeing expressive large-scale drawings at a peer’s thesis exhibition and being impressed by the physicality and emotive qualities in her works. Those qualities initially inspired me to work large scale. I’m still interested in large-scale work that is physical and emotive, but now I’m also interested in scale as a way to dialogue with and complicate masculine narratives and traditions.

BB: Even the two sketchbook studies you gave us were large. Do you always work like that? Do you have a more traditional, smaller sketchbook for capturing quick ideas and thoughts?

PEH: Drawings function for me as either a way to reconsider a painting that’s in progress and/or as pieces in their own right. I usually sketch using my camera, taking hundreds of photos and then manipulating them through various other forms of digital mediation. I’ll make studies from those in various sizes, but I enjoy the space and physicality working the large scale allows.

PEH: Drawings function for me as either a way to reconsider a painting that’s in progress and/or as pieces in their own right. I usually sketch using my camera, taking hundreds of photos and then manipulating them through various other forms of digital mediation. I’ll make studies from those in various sizes, but I enjoy the space and physicality working the large scale allows.

BB: Do you feel any pressure to work on smaller pieces to make the work more accessible and increase the potential market of people who can buy your art? Even putting the issue of cost aside, having pieces regularly over two meters high or wide will impact on its accessibility?

PEH: When I make paintings, my decisions regarding scale tend to be driven by content and context. With concern to size and accessibility, I only think about it when I have to ship it. Luckily, I’ve had the support from institutions for my projects and assistance with shipping my works nationally and internationally.

BB: The Imperfect Colossi series was obviously an emotional exercise for you. This is evident through both the nature of the inspiration and the work itself. The characters emotions are less subtle than the later work and the pain the characters are feeling is easier to read. Was it a hard collection to put together and to exhibit?

PEH: I love story tellers and musicians who tap into their personal experiences and pain to make art that’s visceral and conscious. For three years I struggled with the ideas that would become Imperfect Colossi. I made several efforts to visualize those ideas, but when I hit upon using my own body to speak through, things began to fall into place. With Imperfect Colossi I worked to bring into an art context a subject that was direct, vulnerable, and expressive.

BB: Your work since then obviously deals with personal themes of identity and relationships but these are also more general issues that impact upon everyone. When you work on these pieces are you questioning and attempting to make sense of your own personal issues around these themes or are you talking about the wider human condition?

PEH: To me, questioning one is like questioning the other. I begin every series by pulling from my personal experience or understanding. As the work develops both technically and conceptually, I question how the work is relevant not only to me, but to a larger audience. To clarify, it’s not my intention to dictate to others, but to share an effort to reconcile inner duality and yield to new realities that require constant compromising change.

BB: Following on from that, I suppose the question is why are you creating these works? Are you challenging yourself first and foremost or are you trying to challenge and engage your audience? It certainly seemed the former with Imperfect Colossi.

BB: Following on from that, I suppose the question is why are you creating these works? Are you challenging yourself first and foremost or are you trying to challenge and engage your audience? It certainly seemed the former with Imperfect Colossi.

PEH: When one goes down the road of representation in paint, particularly the figurative and more particularly the nude, there are certain histories and responsibilities to be navigated and acknowledged. What’s at stake here is representation. The nude female has historically been an object and the male has been cloaked in allegory to remove voyeuristic readings for a heterosexual audience. Additionally, nude men of color have been grossly exaggerated or underrepresented from the discourse. Prior to the 20th century, artists of color rarely had the opportunity to place examples of themselves within the lexicon of paint and institutions that hold our artistic heritage. In America, during the 1960s and 70s, artists such as Barkly L. Hendricks presented the world with images of contemporary African Americans and self-representations that were confident, iconic, and complex. These works exemplified the climate of Black Power, independence, dignity, and identity, and were statements of political and social protest. These artists were confronting the deferred dreams of marginalized artists before them while disputing the status quo. Through their efforts, curators, critics, historians and museum-goers have been challenged to reconsider the institution and the representations of blackness, gender and power housed within. The act of painting and subjects I render are caught between collective memory and present experience. By blending traditions of the Old Masters with contemporary modes of representation, I want to explore the tension between power and vulnerability, symbolize my shadow-selves, and present portraits that are racially complex that challenge typical gender roles.

BB: It’s interesting both that you experimented with slip casting and also that you have included it in your retrospective. What inspired you to try that and is it something you have maintained an interest in?

PEH: Yes. I’ve drawn and painted for years, but the residency at the JMKAC opened up new avenues for me to move toward sculpture as well. During my next project that I’ll begin this fall, I plan on experimenting in 3D.

PEH: Yes. I’ve drawn and painted for years, but the residency at the JMKAC opened up new avenues for me to move toward sculpture as well. During my next project that I’ll begin this fall, I plan on experimenting in 3D.

BB: When you went back to painting do you think it changed your approach in any way?

PEH: My studio was a very isolated place. After experiencing a way of working where collaboration was an integral part of the process, it changed my views and needs within my own practice. Since returning to my studio, I began working with some wonderful and talented assistants and have invited a growing number of visiting critics and friends to the space.

BB: Are their any other mediums you are interested in experimenting with?

PEH: There’ve been some interesting advances with 3D scanning technology and it’s becoming more and more accessible – I’d like to play with that.

BB: In terms of your painting process, the images you provided give a fantastic insight into how you build up your work. How may hours go into a piece like that and across what sort of time period?

PEH: Each stage in the “process” images represent one sitting. A sitting might be 5 to 8 hours. For a work that size it’s about a month and a half turnaround from building stretchers to posting it online. I put in about 20 hours a week in the studio putting material to surfaces. The other 20 to 30 hours go toward the business side of the studio and research.

BB: Do you have a few pieces on the go at any one time or do you work on them one at a time?

PEH: I usually work on at least two pieces in tandem, sometimes more.

BB: It’s also interesting that you work in education, teaching and talking about art. It’s obviously a fantastic way to spend your time – inspiring and teaching a new generation of artists. Beyond the satisfaction you get from doing that, do you think it has had an impact on your own work? If so, in what way?

PEH: With the support of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I’ve been able to realize large scale-projects that would have been very difficult without the space, time, and funding they gives me. Speaking with colleagues, grads, and undergrads about art, the art world, and technical fundamentals keeps me sharp and competitive when I’m away from New York and Chicago.

BB: If there was one thing you would like your students to take away from their time with you what would it be?

BB: If there was one thing you would like your students to take away from their time with you what would it be?

PEH: Visual imagery is increasingly becoming the means by which content, information, and entertainment are disseminated and consumed. Generally, art professors are preparing students to hone abilities that could command great power. I hope students take from my courses not only an understanding of how craftsmanship and content can inform each other, but also a sensitivity to their responsibility to avoiding putting unconsidered objects and images in the world.

BB: Did you go through formal art training yourself? If so what was your experience like? Are there specific things you are trying to correct or replicate with your teachings based on your own experiences as a student?

PEH: Yes, I received a BA from Coker College and an MFA from the University of Connecticut. I had a liberal arts undergraduate experience, and had an opportunity to explore artistic expression in a wide variety of media (dance, theatre, choir, piano, graphic design, and of course, fine art). I was also able to explore interests in art education and psychology. My graduate experience was invaluable. I had a large studio for the first time, and made frequent trips to NYC. I had a great critique experience, but at some points, there was limited access to real world business and art related discussions. In terms of critique, I think it’s important to listen to what the student is trying to achieve with her or his work and give feedback that will help achieve her or his individual goals. I try to balance academic and conceptual loftiness with real world, pragmatic advice in regard to students’ own artistic practices.