BY ZINA MUSSMANN + RACHEL QUIRK

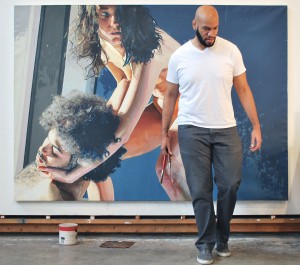

In conjunction with my exhibition Significant Other, the directors of Greymatter Gallery and I discuss figurative painting, representation, and Western Art History. Significant Other will be on display from July 26 – September 21. Read below or view original post.

WITH MY CURRENT PROJECT SIGNIFICANT OTHER, I MOVE TOWARDS ASPECTS OF FIGURATIVE REPRESENTATION THAT HAVE BEEN HISTORICALLY SKEWED, ARE CONTEMPORARILY TABOO, OR UNDERREPRESENTED.

“Night Watch” 68×96 oil on linen

GREYMATTER GALLERY: I’ve always found it interesting how different artists gravitate toward specific mediums. Is there anything about your personality that you think attracts you to painting?

PATRICK EARL HAMMIE: I’ve drawn constantly from an early age, so maybe that oriented me toward 2D. At first, painting seemed like a natural extension of drawing. Now it’s use is tied to my content in terms of questioning and celebrating its history. Recently, I’ve begun experimenting with 3D objects. I’m not sure how those experiments will translate into my vocabulary, but my practice has always been a place where I’ve felt free to evolve.

GG: Could you please tell us a little about your background and how you think that influenced your work?

PEH: I was born in New Haven, CT in 1981. I was raised in West Haven, CT, but moved back and forth between there and Hartsville, SC until graduate school. I did martial arts when I was younger, and participated in concert choir and athletics until college. I earned my BA in Drawing and Psychology from South Carolina’s Coker College and my MFA in Painting from the University of Connecticut. Many of my interests from childhood to now such as comics, science fiction, religious studies, philosophy and music have influenced my work. Many things I’m drawn to engage with universal humanistic plights revealed through personal narratives.

GG: You choose to paint on a very large scale; some of your canvases are 8 feet long. Can you explain how scale relates to the meanings behind your work?

PEH: My decisions regarding scale tend to be driven by content and context. For example, historically there’s been a type of chest beating amongst male artists, manifested in heroic canvases that would reach mural-like proportions. I’m a fan of big works and spectacles like many others, but scale does function as a visual symbol of masculine expression, usually reinforced by the content within the frame. With those narratives in mind, I dialogue with those histories by positioning my canvases within that context, while re-presenting examples of women and men that question constructions of identity, history, and gender politics.

GG: It always impresses me when an artist can use traditional media in very conceptual ways. How do the processes specific to oil painting relate to how you are questioning representations of race and gender?

PEH: Perhaps more than any other form of image-making, figurative painting is often read as a mirror of the time in which it is made; the canvas might be uniquely valued as a type of sociohistorical document. When one goes down the road of representation in paint, particularly the figurative, and more specifically the nude, there are certain histories and responsibilities to be navigated and acknowledged. What’s at stake here is representation. Painting has been a forum where these conversations have lived the longest. Utilizing the medium to critique its practice, I adopt body language, narrative and scale, to participate in this discourse, and to reinvent and remix ideal beauty and heroic nudity.

“Untitled” 42×60″ charcoal on paper

GG: It is very cool that you use traditional painting to critique Western Art History. Would you elaborate on how you accomplish this through how individuals in your work are depicted, situated, etc.?

PEH: When one thinks of figurative art as a contemporary endeavor one may take a skeptical position as to its relevance. For me, figurative art has relevancy. While I deeply respect and appreciate historical uses of the nude form, the ideas and context in which they developed are no longer in accord with our modern understanding of gender, race, sexuality and mythology. While many contemporary artists have made great strides to relocate this ancient and personal form of human expression, the critical mass of uncritical examples by artists trying to capture those past ideas populates the current collective consciousness. We’re left with associations of the “nude” in art equating to female, white, young, thin, shaved, full breasted, and vulnerable or hypersexual.

With my current project Significant Other, I move towards aspects of figurative representation that have been historically skewed, are contemporarily taboo, or underrepresented. For centuries, male painters have historically presented women as static objects represented in a serpentine pose that recalled Eve’s original sin. The male nude has been cloaked in allegory, which aimed to provide forums for culturally sanctioned looking for an understood heterosexual audience. In the absence of allegory, the penis became mostly un-representable as its presence would make vulnerable to critique the idea and signifier of male power. Subsequently, the black male body has been subject to grotesque exaggerations ranging from abject physical features to hypersexual endowment, all of which reinforced white male normativity and command.

With Significant Other, I suggest the two figures as halves of self. They operate for me as individual female and male figures, symbols of feminine and masculine institutions, as well as forms of self-portraiture. I work to present the woman as a doer who is active and agent. She embodies a strength not derived solely from a masculine-centric understanding of strength, but a strength that also valorizes traits such as care and empathy. With the man, I situate him in a vulnerable position where he has relinquished allusions of power. Lighting and paint colors play an important role in regards to race. The light democratized the complexions in such a way as to challenge easy or rhetorical reads of ethnicity. Realistic representations of persons of color by persons of color have been greatly absent in the narrative of painting, particularly nudes. I strive to make room for alternative depictions of race and gender. Drawing from my history as a son, a male and an African American struggling to synthesize past adversity, my paintings symbolize my shadow-selves, and represent an effort to transcend typical masculine ideals and yield to new realities that require constant compromise and change.

GG: These paintings definitely have an intellectual basis, but also have a deeply emotive quality that comes through quite intensely. How do you think these two qualities interact and reinforce one another?

PEH: As cerebral as artists can become, I equally love when artists, storytellers and musicians tap into their personal experiences and pain to make art that’s visceral and conscious. My ideas have always started with my personal experiences, questions, struggles, and interests. Events like my father’s death when I was 17, singing John Rutter’s Requiem at Carnegie Hall in college, or witnessing a milestone in American presidential history, all vibrate in my gut first, then my head. I want to make work that engages people in that way as well.

GG: One last question I like to ask our artists now and again: If you could witness any moment in history firsthand, what would it be?

PEH: I think the most important time in history is now. It might be interesting to witness moments in history such as the first American woman casting her presidential vote, or the circumstances under which my African and European ancestors first stepped onto American shores, but I’m most excited to experience what’s happening right now, and imagining what will be in the future.