BY OILVER ENWONWU AND OYINDAMOLA OLANIYAN

Interview with Omenka, Africa’s premium art, business, and luxury-lifestyle magazine. View original post or read ??

In the third part of our continuing series on artists in diaspora who promote Black identity and pride through their work, we present Patrick Earl Hammie, an African-American visual artist.

Patrick Earl Hammie is best known for his large-scale portrait and figurative paintings, which draw from art history and visual culture to examine cultural identity, social equity, and critical aspects of gender and race. Born in New Haven, Connecticut, he received his BA from Coker College and his MFA from the University of Connecticut.

Hammie’s work is defined by his ongoing engagement with the history of painting. His use of scale, expression, and emotive subject matter recalls elements of the baroque and romantic periods. His interest is partly historical: he studies the pictorial, technical, and narrative conventions of art to explore the ways in which (primarily) male artists have imagined the body.

Considering such conventions in a contemporary context, Hammie delivers fresh ideals of the bodies of people of colour and of women, which both disturb the existing cannon and also normalise the presence of these groups in public art space and discourse. Hammie is currently an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In this interview with Omenka, he discusses his work in detail.

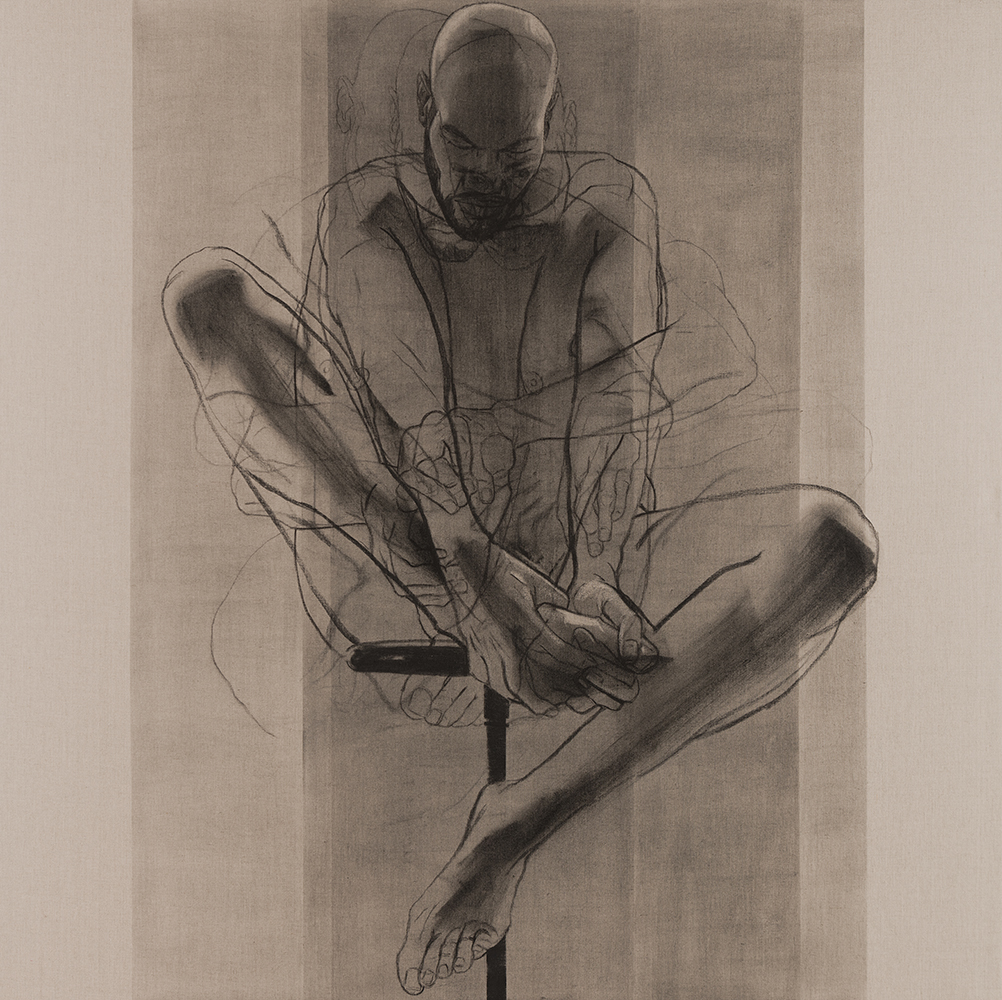

Your BA in drawing is no doubt a solid foundation for your MFA in painting from the University of Connecticut (2008). Please tell us more about this transition, considering that today many scholars and critics view drawings as preparatory for larger paintings and seldom as finished pieces in themselves?

I learned how to think and communicate through expressive mark making and mixed media drawing processes in university. My professors exposed me to artists like Charles White, Sidney Goodman, and William Kentridge. These experiences taught me to see drawing as a significant medium. Presently, I create drawings and paintings in parallel, sometimes with unique, independent subjects, sometimes in tandem. I may work on a drawing months after its matching painting is completed to rethink the subject matter.

Your series ‘Oedipus,’ created in 2007 shortly after you received your BA in drawing from Coker College (South Carolina) may be essentially interpreted as anatomical studies of feet and hands. What deeper significance must we draw from them—should they be viewed as preliminary sketches for larger paintings centred on the Greek mythological figure Oedipus?

‘Oedipus’ (2007) began as a deeply private series that I didn’t initially intend to share widely. They were a way for me to think through my role in my father’s premature death in 1999. He was comatose for two weeks after surgical complications, and it fell to me to pull the plug or risk the low percentage chance he’d awaken in a vegetative state. I chose the former. I found the reference to Sophocles’ character Oedipus, protagonist of Oedipus Rex, to be a starting point. (“Oedipus” is Greek for “swollen foot.”) The importance of feet to the Black diaspora community was also integral, like when Black Union soldiers petitioned during the American Civil War for adequate footwear so they could march and fight for their freedom.

Your series ‘Kohler Residency’ emerged from your time at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in 2011. Why the marked change in direction to sculpture, and what impact overall has the embrace of this medium had on your oeuvre?

I did the John Michael Kohler Art Center (JMKAC) Arts/Industry Residency shortly after my wife and I moved to Illinois from Connecticut and I joined the faculty at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I was learning the art scene and institutions, and the residency is known for its dynamic collaborations with artists and notable alumni, like Theaster Gates and Beth Lipman. I’ve always thought about my figures from a sculptural viewpoint. JMKAC was an opportunity to engage with 3D processes and industrial equipment, and to stretch my practice in a new direction. The work I made was informed by Afro-futurist themes that projected the Black body into the future, and Robert Mapplethorpe’s work on beauty and rebirth.

You are presently an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. How has teaching influenced the evolution of your work?

I travel frequently for my exhibitions and lectures, but when I can’t get away, the community of this research institution keeps me stimulated and fresh. I’ve always sought out new visual experiences and dynamic discussion on culture and production, and working with my colleagues and students feeds that impulse. It’s like a pressure cooker: New ideas bubble up, and old theories are revisited in conversations and lessons. Also, I have access to resources that allow me to make interdisciplinary connections across the university and stay ambitious in my studio practice.

You successfully employ traditional media in many conceptual ways. How do the processes and techniques specific to oil painting translate to how you are questioning representations of race and gender?

Thanks! That answer lies in who’s had historical privilege to use the medium, how subjects have been displayed, and how artists have learned to construct these representations. As I travel and lecture, I encounter many students who aren’t learning complex technical strategies for painting people of colour, or for subjectifying historically marginalised bodies in a contemporary context. I’m a descendant of enslaved people who were never expected or welcomed to use these tools of fine art; the technology wasn’t designed for me. This inconsideration is still prevalent: Kodak’s photo processes prioritized lighter skin, and Apple’s facial recognition software wasn’t optimised to recognise dark-skinned faces. For generations, my ancestors have hacked similar tools and innovated through them. The most dynamic strides towards representing darker skin in films like Selma and Moonlight occurred since the turn of the 21st century. Through oil painting, I hope to share my effort to formally and conceptually challenge these traditions and inspire others to construct new narratives with the medium.

Some of your canvases are monumental in size, with several measuring eight feet long. How does scale convey additional meaning in your work?

The large scale allows me to get my whole body into the process, making grand and fine gestures, and to play between the lines of abstraction and representation. The scale and format are typically informed by the subject, and sometimes by where the work’s going to be exhibited.

The last decade has been a productive period for you, giving rise to several bodies of work, including ‘Equivalent Exchange’ (2009 – 2010); ‘Significant Other’ (2010 – 2015); ‘Birth Throes’ (2014 – 2017); and presently, ‘Counterpoint Project’ (2018). Can you please briefly describe each endeavour, taking care to mention points of convergence and departure?

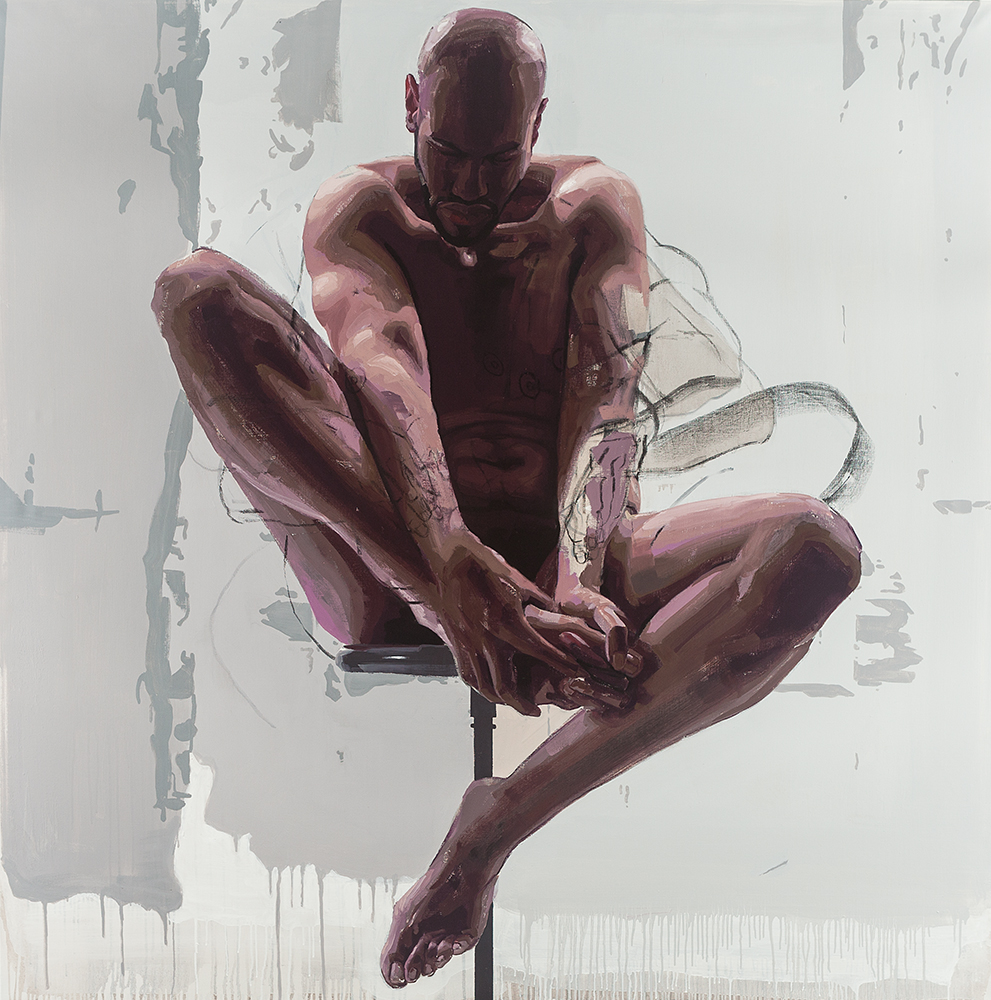

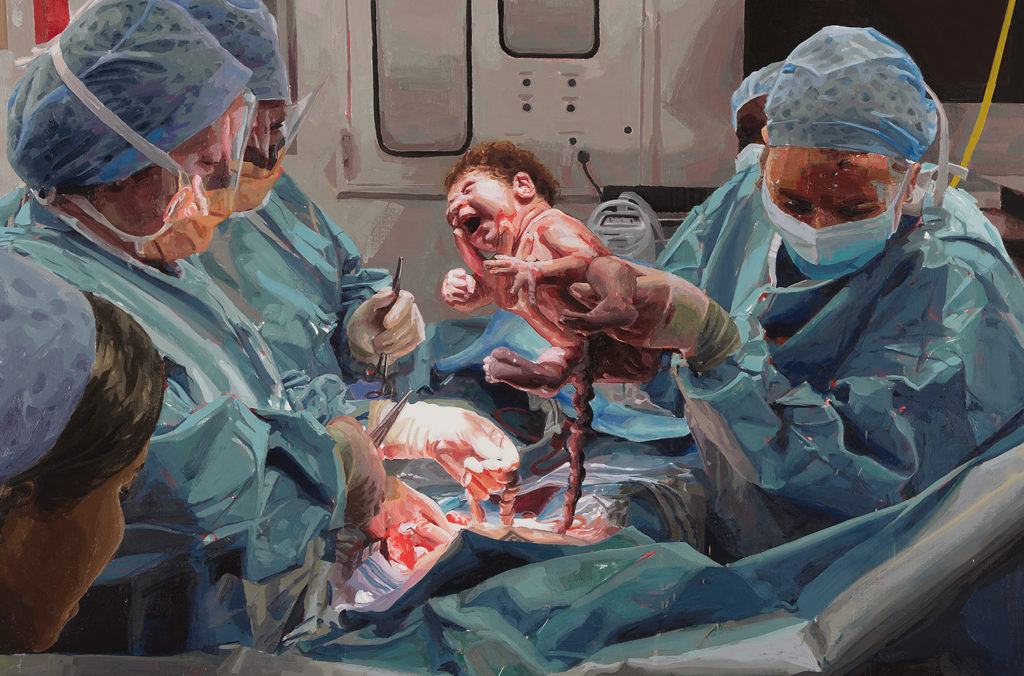

I’m grateful to be this active, and to have worked with so many that have supported my ideas. My artwork is connected through themes related to cultural identity, social equity, narrative, and the body in visual culture. We’ve learned to see Black and brown bodies as threatening, macho, and exotic; to judge and objectify women based on surface; and demonize and outlaw difference from the images we consume and narratives we inherit. I’m particularly interested in constructing ideals that explore the ways we value people of colour and women today. ‘Equivalent Exchange’ examines the vulnerability and promise of a maturing Black identity moving from objecthood to subjecthood. ‘Significant Other’ explores gendered and racial narratives learned from art and media, and remodels the woman as an active authority and eases the man from macho performance. ‘Birth Throes’ reflects on shifting American demographics, and pictures the capacities for Black family and women’s experiences to disrupt, transform, and enhance American culture. For example, Untimely Ripp’d (2017) brings together many of these ideas. It pictures a Black mother and a team of surgeons performing cesarean delivery in an operating room. The painting combines the professional, economic, and emotional labour involved in modern childbirth. This fusion connects the cultural and critical valuing of Black life, in particular its premature ending, through depicting the business of its beginning. The scene of five female surgeons and a mother bearing new life recalls paintings like Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic (1875), and expands examples of active medical professionals and women. The title is a reference to the cesarean-born character Lord Macduff from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, who would foil the tyrant that Macbeth would become. This suggestion provides room to consider the coming Black body as both a warning and a longing for revolution.

Interestingly, examples of work from the series ‘Oedipus’ are included in ‘Birth Throes.’ Why is it necessary to revisit or reinterpret earlier work in this regard?

I found some of the threads begun in ‘Oedipus’ take on new meaning in the context of ‘Birth Throes,’ which, in part, thinks through Black birth and assumptions placed on newborns based on statistics and stereotypes. By blending elements of ‘Equivalent Exchange’ with ‘Oedipus,’ I’m able to tease out the undertones of prophecy, legacy, and struggle against one’s fate inherent in [the story of] Oedipus.

In Stillborn, you depict an adult skull to shock viewers who expect an unborn foetus. Are you alluding to the cycle of birth, death, and decay?

The skull in Stillborn was actually referenced from a medical photo of a stillborn baby’s skull. I made three versions, all open to typical interpretations of memento mori. Personally, it allows me to think about my mother’s first child, a stillborn older sister I’ll never know. I hope there’s also space to consider it symbolically as stunted or deferred hopes that people and communities mourn, remember, and work to rekindle.

Another point of interest is the titles you give your works: some, like Icarus, Hel, and Aureole, betray a deep engagement with mythology; others, like Nadir and Slant, refer to the emotional and physical in human existence. Kindly expatiate on these observations.

I’m fascinated with many mythologies, and how our stories have both unique, provincial meanings and also universally accessible ones. I pair some of my works with these titles to provide an entry point from which to consider the subject in the now, and across time and cultures. I believe what captivates us with tales that concern gods is what feels most human about them, how they root us in our history and reflect us.

What informs the selection of your models? Are they randomly selected or do you share personal history with them?

I typically work with people I know: family, friends, or other artists. There’s something more familiar that translates into the work. When I do work with more “traditional” models, it’s important that we’ve built up a relationship over a few years where they’ve been involved in conversations about the work or specific project.

You appear in several of your works, most notably your series ‘Equivalent Exchange.’ Is casting yourself in your paintings a strategy to deal with contrasting identities and influences in your life and why?

The work begins with me filtering my experiences and examining what’s happening in the world. Early on, it was pragmatic to use myself: I was convenient, and I’d only subject another to something I’d expose myself to. I learned how my body’s story could communicate my thoughts, and developed that knowledge to understand how to work with others and their bodies. Self-representation, and broadening the representations of people of colour in art, is critical to me.

At what point in your career did you realise it was important to project the Black race positively, and was this decision informed by personal experiences?

From the beginning, I worked to present dynamic and complex Black male bodies. More recently, I have expanded to include representations of women. I’m driven to expand the types of portraits and artists that patrons encounter and expect when viewing art. I realize a way to impact entrenched ideas and methods is to normalise the Other (and those who’ve been historically marginalized) by exposing viewers to a critical mass of difference, and to challenge stereotypes through subjectifying stories.

In your most recent body of work ‘Counterpoint Project,’ you explore the ongoing cultural and critical contributions of Black ballerinas in dance and visual culture. Please tell us more about this series and what inspired it.

‘Counterpoint’ is a collaboration with dancer and choreographer Endalyn Taylor. We worked with five ballerinas, a clothing designer, a documentarian, and MoBBallet to present a public performance, panel discussion, website archive, and artworks that highlight and reframe Black ballerinas’ contributions to dance and visual culture. The concept first came when Endalyn and I spoke together on a panel about mastery. We connected through our disciplines’ roots in European elitism, and how ballet and visual art have shaped each other for centuries. Our shared thoughts on art, excellence, and the history of professional African-American women seemed a natural fit for collaboration. We premiered ‘Counterpoint Project’ last May (2018) at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. Inspired by an Afro-Brazilian dancer we worked with, we’ve discussed centring the next iteration of the project in Brazil.