BY ALICIA BARBAS

Alicia Barbas at The Daily Illini, interviewed Laurie Hogin, Guen Montgomery, and myself about our work in the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s School of Art and Design Faculty Exhibition at Krannert Art Museum. View original post or read ??

BY ALICIA BARBAS, STAFF WRITER

DECEMBER 2, 2018

Filed under Arts & Entertainment, Life & Culture

For generations, artwork has spoken to American society in ways that words cannot express. The political climate experienced by each American artist during their lifetime often impacts the content, messages or themes in their work, and this truth is exhibited once again at the University.

On Nov. 1, the University’s School of Art and Design launched its annual Faculty Exhibition at the Krannert Art Museum. The exhibition will be on display until Dec. 8 and displays faculty members’ original work.

Laurie Hogin, professor and chair of painting and sculpture in the School of Art and Design, was a participant in the exhibition.

“The Krannert Art Museum facilitates our public service by hosting this annual show,” Hogin said. “This has really been going on for generations.”

As a part of the research campus, the museum hosts the exhibition but does not curate it, meaning each faculty member freely chooses which of their pieces is displayed, often surprising even their colleagues, Hogin explained.

Guen Montgomery, lecturer in the School of Art and Design and participant in the exhibition, sees it as an opportunity to be more experimental and build on ideas she has been thinking about.

“It includes a lot of studio faculty, but also people in design and art education,” Montgomery said. “I’m not the only printmaker who has work in the show either.”

As a result, there is quite a mix of art materials; from oil on canvas to painting, printmaking and sculpture. While each piece sends a unique message, many of them seem to make statements on current politics, societal perspectives and personal identity.

“I like to loan works that will speak to students particularly, in some kind of way,” Hogin said.

Montgomery explained there is a diversity of themes in the exhibition rather than a common one, though many pieces have a political undertone.

“If there are similar themes, it’s because we’re all living in the same historical moment and responding to the same conditions,” Hogin said. “That’s one of the interesting things about art; it’s about the individual navigating their own waters and responding in real time.”

Patrick Earl Hammie, associate professor in the School of Art and Design, described the strength and flow of this exhibition.

“We do such different things,” Hammie said. “And this is definitely one of a few shows that feels very strong, very cohesive, even though we’re not working under any particular theme.”

As an observer of this exhibition, the first piece that may stand out is Montgomery’s, as it occupies a large portion of ground in the first room.

Montgomery’s work consists of screen printing patterns on commercial tents and ottoman stools. She tends to use a hybrid form of art that isn’t purely printmaking and cannot always be traditionally displayed.

“I don’t always feel like two-dimensional space is enough,” Montgomery said. “I wanted to break out of that and off the wall.”

As an artist, Montgomery has a background in theater, through which she cultivated an interest in props and scenery. This helped her convey a deeper message through her work.

“I’m thinking a lot about humanity’s relationship to stuff,” Montgomery said. “I think about how we crave material objects and how we fill ourselves and a sense of psychological absence with possessions.”

To Montgomery, the piece is about the tension between wanting these material items — many of which are not necessary for survival — and wanting to escape them through the act of camping.

“Camping is kind of a privileged activity,” Montgomery said. “There are people who camp out of necessity every day; people without homes or more who live nomadic lifestyles.”

The concept of privilege in camping culture is heightened in the fact that people of color tend to dislike it due to historical violence, Montgomery said. Through this, the piece becomes political and relevant to current societal consumerist ideals.

A similar political criticism is found in another prominent piece: Hogin’s trilogy entitled “American Trilogy #1: A Jingo Monkey About to Devour a Piece of Cake,” “American Trilogy #2: A Jingo Monkey Beating the Skull of a Patriot” and “American Trilogy #3: A Jingo Monkey Surprises Himself,” in which the monkey holds a gun.

Hogin, who is known for her allegorical animals, describes her work in the exhibition as a piece of “lament over the fact that our worst tribalist tendencies are destroying our political discourse.”

Hogin explores the ways in which humans have a blind, unthinking sense of belonging to certain groups, especially in today’s political climate, and the ways in which they express that sense of belonging.

“The monkeys are kind of cartoons or stand-ins or allegories for human beings,” Hogin said. “In the middle ages, monkeys represented human sinfulness, as instinct, desire-driven creatures that don’t really have much of a conscience.”

Hogin mentions that she herself is a patriotic person, but that a sense of blind patriotism is prominent in today’s American society and has caused a betrayal and abuse of freedoms, such as the right to bear arms.

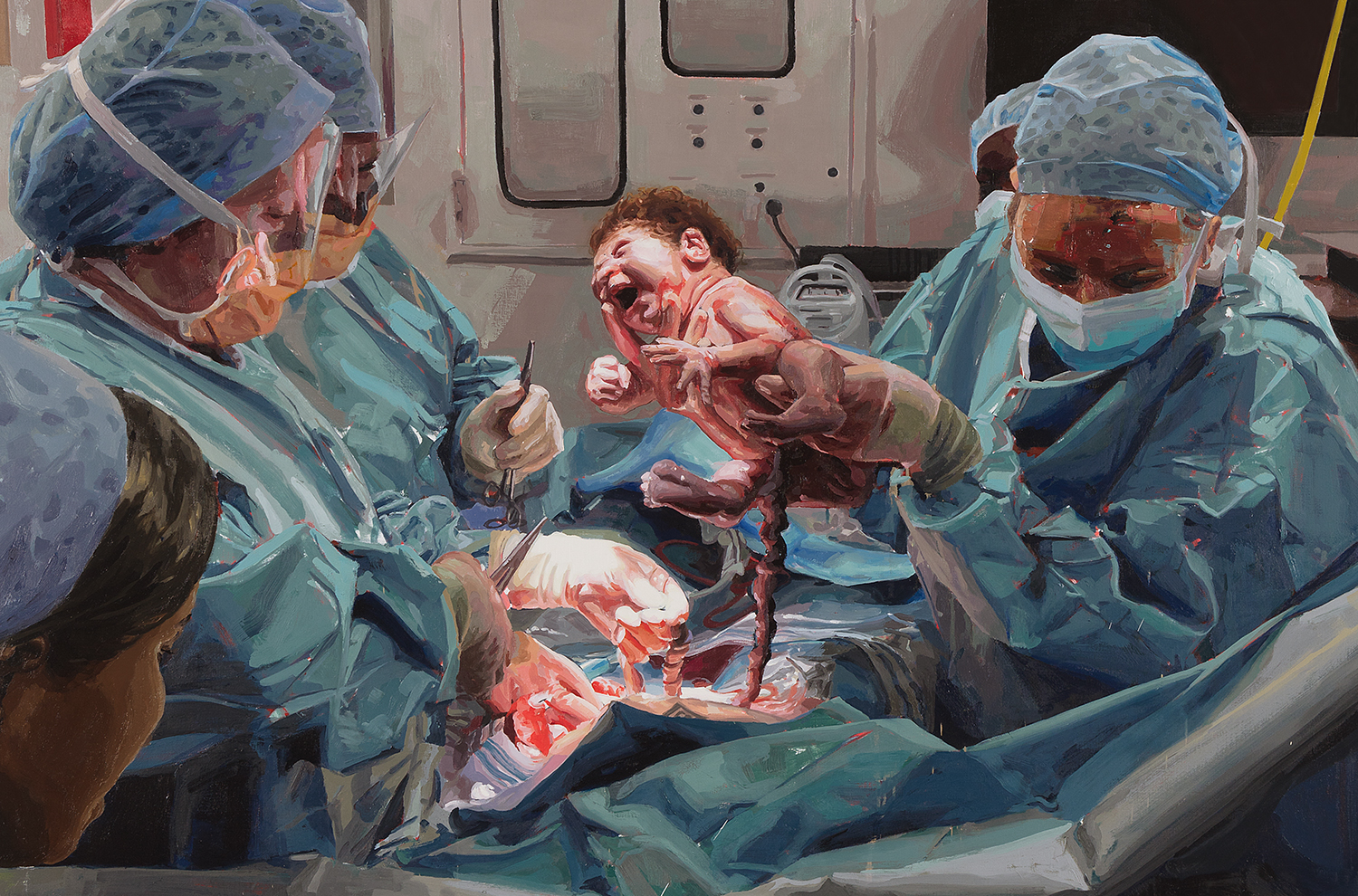

In the flow of the exhibition, next to Hogin’s painted criticism of political discourse is Hammie’s depiction of a cesarean section birth scene.

Having examined the traditional expectations of beauty and painting in museums, Hammie explained that he took a realist approach to the scene.

“With this piece, I really wanted to represent five medical professionals, who are women, and a mother at a grand scale in an institution like a museum, that spoke to women as medical professionals, as surgeons and nurses, historically where they weren’t, doing what historically we don’t expect them to do in art and bearing new life,” Hammie said.

The newborn child in the center of the painting is meant to represent Hammie himself, who was born through a cesarean.

“This was a moment where I really wanted to picture black birth,” Hammie said. “The piece brings together so many different forms of labor. The psychic, emotional, professional, financial effort that goes into bringing one life into this world and, in particular, one black life. Hopefully if one can consider all of that, it could give a new perspective to what it means to rip a black life from this world.”

Though Hammie does not consider it a political piece, there are certain social ideologies that created a basis for it, including how women are represented, painting’s history, and values of black people and marginalized groups. People can then bring their own political ideologies and opinions to it, he said.

Because of the non-traditional basis of the piece, Hammie explained that there may be cases in which the painting brings out uncomfortable topics for specific people to discuss.

“I’ve always been a believer that it’s important to move toward things that are difficult,” Hammie said.

By creating pieces that bring up these questions, hopefully viewers confront realities, question the way they’ve perceived history and reconsider the assumptions they bring to a piece, he explained. Even questioning what you expect when you enter a museum or who you expect the author of a piece to be can shed light on these assumptions, Hammie said.

The exhibition not only displays the artists’ original pieces as works with current themes resonate with the community, it also offers an opportunity to teach and inspire students.

“There’s a relationship between what I do in my studio and what I do in the classroom,” Hogin said.

Hammie often includes some of the same social topics used in his work in class discussions and assignments he gives.

“There’s also a kind of bravery with exhibiting your own work,” Montgomery said. “It really is putting your money where your mouth is in terms of your ability to communicate what is valuable in the world of art and design and then also show that you yourself are participating in that world.”

Montgomery explained that being able to see instructors practice and exhibit their work hopefully creates a contagious sense of courage and self-confidence in students to create their own work.

Seeing the work of talented students is what inspires Hogin herself to continue creating.

“It’s about seeing that spark in a student’s eye when they realize what they can do with paint,” Hammie said.

abarba9@dailyillini.com